CO2 from Biomass is Not Different?

Burning coal, oil and natural gas releases CO2 => that's BAD because its fossil fuel.

Burning biomass releases CO2 => that's OK because biomass is a renewable resource and biomass is 'carbon neutral'.

This doesn't make sense! How can the carbon dioxide from biomass be treated separately and partitioned into a separate bubble in the atmosphere? There have been recent plans all around the world to use concept that burning biomass is 'carbon neutral' to develop wood burning power stations and they get incentives from Governments because it is regarded as a renewable resource, despite the fact that trees take 30-60 years to regenerate!

The argument that biomass should not be counted as a carbon dioxide sources goes like this (see the image below).

About 11% of the world’s energy comes from biomass; about half of this being wood. Burning of fossil fuels is a major cause of increasing atmospheric CO2, which in turn is a major cause of global warming(climate change). The CO2 from fossils fuels cannot be replenished in anything less than geological time scales and the increase in the levels of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere is essentially a one-way process that is irreversible(1).

Burning wood and other biomass also releases greenhouse gases during combustion (2). However, burning firewood that has been grown in sustainable wood production systems can significantly reduce greenhouse gas emissions, compared to emissions from non-renewable energy sources (?).

This is because unlike fossil fuels, biomass is a renewable resource and the CO2 released from burning biomass can be re-sequestered in subsequent rotations. Sustainably managed forests and plantations that are regrown therefore have a dual benefit:

- they are claimed to be effectively carbon neutral;

- the wood biomass can be burnt to generate energy e.g. firewood. This supposedly eliminates the greenhouses gas emissions that would have resulted from the alternative of burning fossil fuels.

How Can Wood be Carbon Neutral When Burnt?

This argument does not make sense and the notion that biomass is 'carbon neutral' is leading many developers to build biomass burning energy plants - and they get Government incentives to do so because it is regarded as renewable energy - What a joke!

In the United States, about 45 billion kilowatt-hours of electricity is already produced from biomass, about 1.2 percent of the total electric sales. About four billion gallons of ethanol is also produced from agricultural products, about 2% of the liquid fuel used in cars and trucks.

The Department of Energy estimates that the United States could produce up to 4% of transportation fuels from biomass by 2010, and as much as 20 percent by 2030. For electricity, the U.S. Department of Energy estimates that energy crops and crop residues alone could supply as much as much as 14 % of our power needs. But what about accounting for the carbon dioxide? Is biomass really carbon neutral?

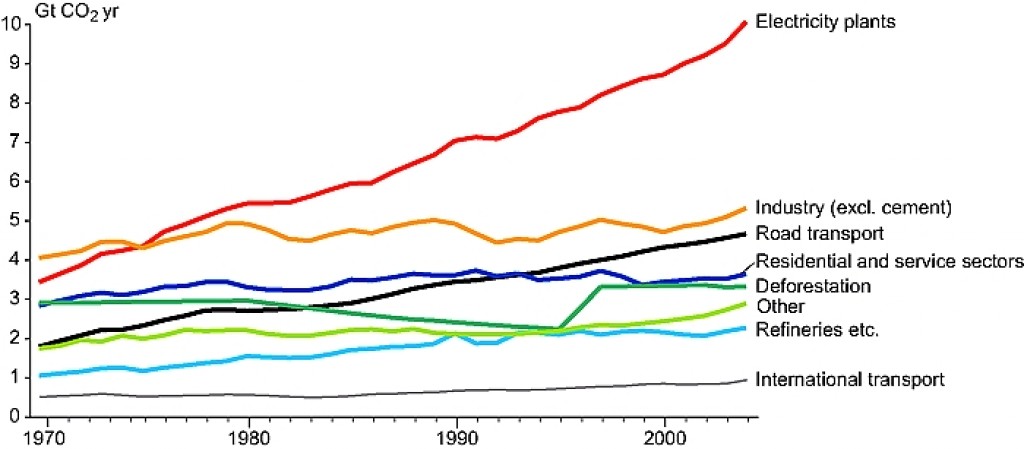

Traditionally the major concern with burning biomass has been the extensive burning associated with the clearing or rainforests and other land areas and the huge amounts of CO2 released from these practices. Carbon dioxide from burning biomass makes a substantial contribution to CO2 emissions and it is rising. (See Figures)

The energy industry and various Governments around the world describe the timber that is being burnt simply as 'forest waste'. However, all of the following materials can be classified as forest waste and could potentially be burnt for the production of electricity.

- Old trees, not suitable for sawlogs ( perhaps 60% of trees harvested in clear-felling),

- Silvicultural thinnings (trees removed to promote the growth of sawlogs)

- Branches, sawdust, bark, tops and butts (these materials may be unsuitable for wood-chipping for paper)

- Whole trees currently used for woodchips from plantation timber

Between 55% and 85% of what is logged from native eucalyptus forests in Australia is already declared waste and turned into woodchips. However there is a major time issue here. In Australia for example, mature pine trees are harvested for large diameter saw logs at 30 to 50 years of age, depending on site conditions and growth rate. Trees harvested for other uses, such as smaller logs, pulpwood are generally harvested much earlier, at 30 to 35 years. The clear felling of native forests occurs in 60- 80 year cycles. The forest is clear-felled with perhaps 60-80% of the native trees deemed unsuitable for timber. Many of the pine plantations are clear-felled for wood chips. The unsuitable trees and waste is processed for wood chips. So if the wood chips and timber is burnt for power it is going to take around 30 years for the pine trees to be regenerated and store the carbon burnt and perhaps 60 years for native forests.

The result of this time delay could be a huge carbon deficit. (see figure). The burning of timber biomass has to be seen in the context of carbon sequestration and the locking up of carbon in vegetation and the soil. As a side issue the concept of using timber as a source of fibres of microscopic size doesn't make much sense. It involves taking all the structure and strength in a piece of wood and breaking all this structure down to release all the individual fibres. Surely there are better sources of fibres for paper?

Globally there is a push grow timber as an offset for the burning of fossil fuels and to pay third-world countries to stop clearing of rainforests. Does the notion of carbon neutrality mean that these forests can be burnt for energy.

Likewise there is a move to count native forests as carbon stores and to count regeneration of degraded areas as carbon sequestration. Again can these areas be clear-felled for burning? The other point is that sugar cane is an annual crop and so the carbon cycling is clearly demonstrated. However the regeneration cycle for native forests is around 50 years and 25 for pine plantations and how can we guarantee that these forests will be re-grown?.

Clearly there is a large time delay and lack of guarantees when the CO2 debt will be repaid (if ever). The concept is that the CO2 emitted will greatly exceed the amount consumed by the growing trees and lead to a massive debt in CO2.

Wood Fired Power Stations

CO2 Debt

Recently a number of power plants have been developed or planned by claiming they will only burn wood trash - offcuts and timber that is unsuitable for milling.

Once again this is justified as the timber is renewable. This could have major consequences globally if wood and wood chips are increasingly used for power generation. In Australia the production of wood chips for paper manufacturing from native hardwood forests was initially promoted as a way of dealing with all the waste timber from timber processing.

But now it is a major industry that involves entire forests being clear-felled and chipped, with mountains of wood chip being exported annually. Up to 60% of timber from native forest is deemed as not worth milling.

The Tasmanian native forest timber industry is especially dependent on the woodchip exporting industry. About 75 per cent of native forest logs harvested in Tasmania goes to the woodchip trade, and about 93 per cent of the plantation hardwoods.

In East Gippsland, Victoria, 85 percent of forests ends-up as woodchips with only 15 percent of the trees regarded as usable sawnlogs.

In NSW and Tasmania, as much as 95 percent goes to woodchips or waste. The woodchip industry was developed to use waste but now the majority of the timber is 'wasted'!

What's next? Will we see the ships carrying coal from Australia for power stations in Japan and China replaced with ships carrying wood-chips for power stations? What a waste? What a con?

Should Biomass be regarded as Carbon Neutral?

The term "biomass" includes a wide range of organic fuels derived from agriculture, timber, food processing wastes, garbage, sewage sludge and manure. It also includes fuel crops grown or reserved specifically for electricity generation.

Biomass power plants already generate 11,000 MW in USA - the second largest amount of renewable energy in the nation. There is a growing interest in USA and other countries for the development of large biomass plants as the fuels are renewable. But why is biomass burning permitted when it is such an obvious source of carbon dioxide and there is a major push to grow trees to lock away carbon dioxide to offset carbon emissions? There is also a lot of interest to fund third-world countries to stop or reduce the clearing of rainforest and to conserve vegetation communities and to count soil carbon and carbon in vegetation as part of the carbon emission reduction strategies.

Research has shown that emissions from biomass burning have increased by 3-6 times in the last 100 years, mostly because increasing rates of deforestation and burning of forests, grasslands and savannas in the tropics.

The historic data also indicate that the production of greenhouse gases from biomass burning has increased recently.

Recently the EPA in America said the 'tailoring rule' would not exempt biomass producers from carbon regulation, meaning the energy source would fall in the same fossil fuel league as coal and other traditional power sources. The “tailoring rule” that outlines how the agency will regulate greenhouse gas emissions (GHG) under the Clean Air Act. The rule specifies which CO2 emitters will be required to account of their greenhouse gas emissions when the EPA starts regulating the gases from January 2011. The ruling did not exclude biomass-fueled power producers from the need for GHG permits.

Previously the combustion of biomass was regarded as “carbon neutral,” in regulation and policy in the United States and abroad. However concern over the carbon deficit has lead to a change in the way biomass is considered and may mean that the burning of biomass may require explicit offsets in terms of carbon storage. Many existing biomass power plants, in Michigan, California and Maine have objected to the decision. In many cases, those plants benefited from various renewable energy tax incentives or other benefits, to encourage renewable energy initiatives.

The new proposals would require the projects to provide substantial short-term greenhouse gas offsets and may require better definition of the materials used (such as 'residues' and 'waste wood'). Accurate accounting principles are a necessary component of biomass development. Meeting CO2 reduction targets will require full and accurate accounting of all emissions sources.

Regulations for biomass-based fuels, including ethanol were developed recognising that the emissions impacts or various types may vary and should be include life cycle emissions analysis. Internationally, the U.N. has determined that biomass-based energy must be assessed on a specific case-by-case basis. The IPCC also acknowledges that when trees are cut for biomass energy, the loss of carbon from the whole tree must be accounted for.

Opponents have challenged the decision and have pointed out that biomass provides about15% of USA's renewable power and that the Department of Energy expects biomass consumption to double every ten years through to 2030. They argue that it will be difficult to meet ambitious renewable energy goals without biomass.

Conclusion

Hopefully, common sense will prevail.

ALL carbon dioxide from ALL sources needs to be accounted for and offsets must be real and matched with emission rates within appropriate time frames to avoid CO2 debts.

The debate continues!